Crosstown High was founded in 2018 after a Memphis parent spotted a billboard advertising the XQ Super School Project, a competition held by the XQ Institute to reimagine and redesign the American high school through a grant. While Crosstown High wasn’t selected as one of 10 Super School Projects that year, community members continued to build a model for the school and eventually partnered with XQ to become one of more than 60 experimental XQ Schools across the nation. The XQ Institute was started in 2015 by Emerson Collective President Laurene Powell Jobs with Russlynn Ali, former US assistant secretary of education for civil rights, with the mission of disrupting high school design through its guidelines and funding.

Crosstown’s Executive Director Chris Terrill, and Michele Cahill, a senior advisor at the XQ Institute, talked to Bloomberg CityLab about the challenges that come with building a school from scratch – and what can be learned from thinking about education in a completely new light. The interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Chris, how did you get involved with XQ?

Chris Terrill: Around 2016, Memphis was looking for something different in their education system, which is one that is in constant struggle. If you look at the statistics, you’ll see that our students have done historically very poorly on standard measurements of success, with low ACT scores, low graduation and high absenteeism. We were looking for something different in the market that was going to meet students’ needs where they were at.

There was this idea to build a high school in Crosstown Concourse, which is this massive 1.5 million-square-foot facility that was empty for a long time. It started as a Sears distribution and retail center, but then as Sears declined in the neighborhood, it did as well. I knew of the XQ contest, but was not involved in the writing of the grant.

In 2017, I was hired for the position the same week we received the notice that we were not going to receive the award. We stayed in touch with XQ and took that early work that the community had done and started to build for launch. At some point about six months later, XQ came back and said, “You’ve continued to do this work without any kind of funding. We’re going to support you with a minor planning and startup grant.” That was huge for us, as we were developing the school. Then over time we continued to build that relationship with XQ and bought into the principles and ideas along the way as a foundation for building a great school.

What made project-based education a priority for Crosstown?

CT: The only school reform that has happened in Memphis in the last 50 years has been a no-excuses model that was built around just grinding, grinding, grinding – extending the school day, extending the school year, taking things that students were not good at and just giving them more of it.

If you look at the history of education in Memphis, it’s a sad story. Brown v. Board of Education in Topeka, Kansas, happened, but it didn’t really take hold in Memphis until the ‘80’s. When it did, they desegregated schools one grade at a time. Schools were really never desegregated because private schools kept on popping up and there was a separation. Then the charter movement came into Memphis and was largely based on that no-excuse model. So we were looking for something that was unique in the market, something that valued student voice and choice, something that was going to make learning relevant to kids.

Michele Cahill: High school has to change, because the world has changed so much. Young people need academic capacities, knowledge and skills, but they also need a broad range of skills. I mean, how much more evidence did we get about an uncertain world than the pandemic? Many people had given up on high school as too late, and emphasized early education. Of course we believe in that, but what we know from the science of learning is that adolescence is also a peak period where the brain is malleable.

To unlock students’ potential, you need to design schools with certain kinds of guiding principles. Part of the notion of project-based learning is making young people involved in the purpose of learning. You can integrate academic content with the building of cognitive and social-emotional capacities and skills, all of which are needed for young people to have success in post-secondary education, careers and life.

How does Crosstown build a diverse student body and what have been the effects from that?

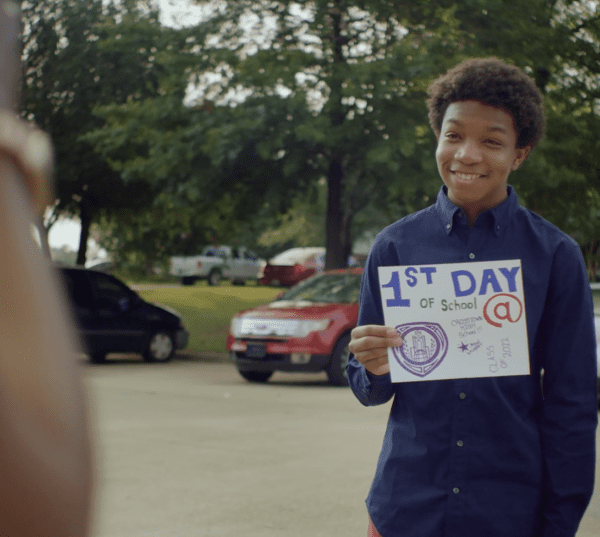

CT: One of our key principles is that we’re a diverse-by-design school. That’s something that we take exceptionally seriously. We actively recruit in every single zip code in the entire county. I think according to our most recent count, students coming into our freshman class are representing something like 79 different middle schools.

Without question, we are the most diverse high school in the entire city of Memphis and possibly the most diverse in the entire state of Tennessee. We use a program called SchoolMint that is a lottery-based system, but we see live data when a student applies for a spot at Crosstown. If we see that there are some neighborhoods that are underrepresented, we can specifically go into that neighborhood and target our marketing to build those numbers up so that we’ve got a real representation of the city of Memphis. There are no prequalifications, so a student doesn’t have to test at a certain level. They don’t have to be at a certain economic level. We feel like if we do our work on the front side and have a representative pool in the lottery, then as long as the lottery gods hold true, then we’ll have that representation across our student body.

What have been the greatest lessons that you’ve learned since the school opened in 2018 to now?

CT: I think we tried to do too much too quickly. We threw a whole lot of things on the wall. Some of them stuck well and have become real key components of our program, but then some didn’t. One of the things that XQ gave us the latitude to do was to try knowing that there were going to be opportunities for improvement and failures along the way. So I think the first thing that I would say would be, “Don’t be afraid to try things that might fail.”

Just like with any startup, sometimes you start with a group of people in a bar writing ideas on napkins with big visions. After that, you start thinking, “What are the impediments to actually implementing these big ideas?” Working through those impediments is something that is super important. If you can take the time to break things down, then you can figure out ways to get to the end goal.

Are there any other innovative approaches to high school education that you admire and seek to model after?

CT: I think that one of the beauties of the XQ blueprint is that it’s curriculum agnostic. It allows for great opportunities for development to meet the needs of your community. So what an XQ school looks like in Memphis is significantly different from what an XQ school in New York or LA might look like. It’s really about understanding the needs of your community and then working to develop a plan that best suits those needs. There’s XQ’s Design Principles, which are the principles that you should implement to have a really strong, highly functioning school. These are things like a strong mission and culture, an emphasis on meaningful and engaged learning, intentional, caring, trusting relationships, youth voice and choice, smart use of time, space and technology and strong embedded community partnerships.

MC: There are now more than 60 schools affiliated with XQ. We have some schools that are hybrid in terms of project-based learning and other forms of teaching and learning. The Grand Rapids Public Museum School is located inside a public museum. Then you have XQ schools in DC that are focused around entrepreneurship. So you have different approaches, but they all work towards the North Star of XQ’s Learner Outcomes and Design Principles.

While not all XQ schools are charter schools, Crosstown High is. Charter schools are often at the center of controversy in the US, with critics arguing that they divert resources from public schools and are selective in their admission process. What are your responses?

CT: That’s a very old argument. The first charter school was created 25 years ago. At the time, you were taking public dollars from kids and that’s not really the case here. We’re still a public school. We’re beholden to the same outcomes and expectations that any other school in the state of Tennessee is held to. We take the same standardized test that the school down the street takes. We operate a similar length calendar and school days. Our teachers are part of the state retirement plan. In the last month, we’ve had four different traditional public schools bring teachers and administrators across town to spend the day with us to look at different techniques.

We’re teaching our students to be generous collaborators, and we’re modeling that generous collaboration with our partners in school districts. I recognize that depending on where you’re at there are different tensions. Right now in Tennessee, the tension isn’t between charter schools and public schools. Our legislature is debating whether or not vouchers should be applied for every student. So a student could take a $7,000 voucher and go to a private school. I think that tension is sometimes a mechanism to take people that typically believe in the same thing and divide them. The sooner we can get past that argument, the better off our kids will be.

What do you see as Crosstown’s role in the broader Memphis community?

CT: We see our role in the broader Memphis community and in the national view, as evangelist for an effort to rethink high school as a whole. We start with that locally, and then take that nationally, but so much needs to change. The XQ concept was developed before the widespread use of ChatGPT and other AI-enabled programming issues. I think things are only going to move faster going forward. We’ve got to prepare students to enter the workforce and solve the complex challenges that are going to be facing the world in the future.

What we do now in education is based upon the Committee of Ten, which was developed 120 years ago. The idea of Carnegie Units, student seat time and the length of the school day were developed 120 years ago. Now more than ever, there needs to be a shift. We need to be thinking about things in terms of competency and development. If you have mastered the English language by the end of your ninth grade year, should you have to take the same thing that everybody else has to take for the next three years, when you should be able to move on and do something different?

What recommendation would you give to other communities or groups who also want to reinvent high schools in their neighborhoods?

MC: Start with your young people. Listen to them and understand where they believe they learn things, how they learn and what their aspirations are for the future. Then ask, what is the future challenge? What is needed today in this dramatically changed information world? What are the opportunities available to students and what are the disparities that exist? For example, when we have done what we call our Educational Opportunity Audit, we have seen that in some states and cities, up to 70% of students haven’t taken the courses that they need to be eligible for a four-year college.

Secondly, look at those Learner Outcomes. What is it that you want, and what do families and the community see as what students should know, and be able to do when they graduate from high school? Then use the Design Principles to go through a process of renewal and redesign. There are all sorts of resources, capacity-building, design briefs, technology-based and competency resources that are available through XQ and other places. But it has to become a movement for transformation by communities if our young people are going to be able to have futures of opportunity, and if our country is going to be strong enough to have a robust economy and democracy.

Music + Art

Music + Art Food + Drinks

Food + Drinks Wellness + Care

Wellness + Care LIVE + STAY

LIVE + STAY EVENTS

EVENTS Our History

Our History