A movie rental shop closing in 2014 was a familiar story. But one opening in 2019?

Welcome to the man-bites-dog tale of Memphis movie culture. After five years of dormancy, four different storage spaces to house a north-of-30,000-title VHS/DVD/Blu-Ray collection, three potential locations that didn’t pan out and two false starts, this countdown has arrived at the return of one of a kind: Black Lodge Video — now just Black Lodge — is back.

Named for a mysterious location in David Lynch’s television series “Twin Peaks,” Black Lodge first opened in 2000 in a little house on a hill in Midtown’s Cooper-Young neighborhood, lasting for 14 even-then-surprising years. On Sept. 6, much like the Lynch series itself, it made an unlikely return.

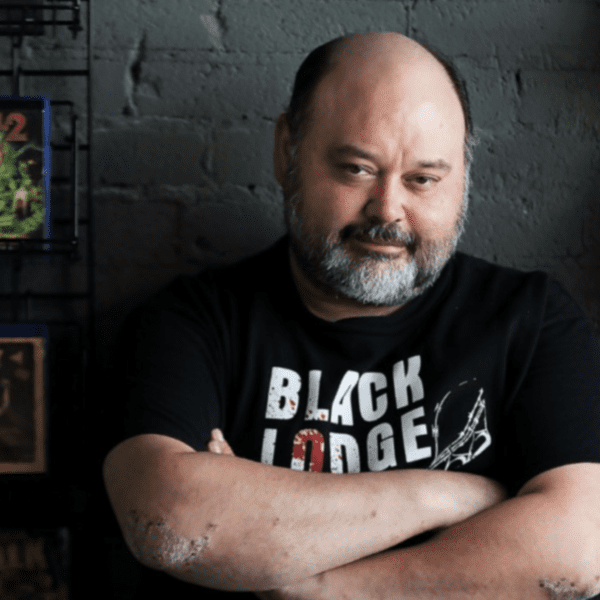

The comparatively mammoth new Lodge is an 8,000-square-foot multi-purpose store/venue/hangout spot at 405 N. Cleveland St., in the Crosstown Arts District. The heart of the enterprise is the more than 20,000 DVD and Blu-Ray titles belonging to co-founder and co-owner Matt Martin. (Like the “Video” in the original name, some 10,000 VHS tapes from the old Lodge did not make the move.)

This collection — or its cover art — is arranged on racks, separated into conventional genres, but also more esoteric and/or evocative categories: “B-Movies & Drive-In,” “Cult Flicks & Bizarre Arthouse” and “Martial Arts & Asian Action.”

You can get new releases and blockbusters, but you can also find a well-curated collection of Hollywood classics, American auteurs, pulp fictions and foreign cinema, as well as oddities with titles such as “Hot Rods to Hell,” “Mafia vs. Ninja” and “Disco Godfather.” These are all available to rent at $4 a pop, a maximum of four titles at a time, or unlimited rentals (still four at a time) for a $10 monthly membership.

But the new Lodge also features film screenings and live performances, with arcade gaming just around the corner and a bar/café somewhere on the horizon.

You may ask yourself: How did we get here?

Martin had co-founded Black Lodge with partner Bryan Hogue as an unconventional conventional video store, but by 2014 it was starting to morph into a cramped venue of sorts, with screenings, live bands and other events.

“Netflix had emerged. RedBox had come about. All the brick-and-mortar (video stores) were dying. I didn’t know how much longer we could get by just renting movies as our only real revenue stream,” said Martin, now 45. “My idea was to find a bigger place. Bryan was ready to do something else.”

Hogue bowed out, striking a deal to let Martin keep and eventually own their shared collection. The Lodge went on a hiatus that was not meant to last so long.

Martin looked at a space on Madison Avenue, adjacent to —and perhaps including — the late and semi-legendary Antenna Club music venue. He looked at a spot around the corner in Cooper-Young, in the same strip as the simpatico Goner Records.

Martin remembers this period as “a chase of never-ending disappointments.”

Eventually, filmmaker Craig Brewer, a longtime friend and Lodge patron, connected Martin to Crosstown Arts’ Chris Miner, who, with partner Todd Richardson, was helping develop not only the Crosstown Concourse space but the surrounding neighborhood.

“To my great happiness, almost instantly Chris Miner got it, what we wanted to do in combining video rental with a space big enough to do shows,” said Martin.

Through Miner, Martin looked at the now-empty Cleveland Flea Market space across from Crosstown Concourse, but that didn’t work out either.

Black Lodge finally found its current home a little farther south in the Crosstown Arts District, a space that had once housed the gay bar Mary’s but which had mostly been empty in recent years.

According to Richardson, Crosstown Arts took over the master lease of the building and took on the responsibility of working with the building owner to rehab it, subleasing to Black Lodge as operator. Twice — in the fall of 2017 and again in the spring of 2018 — the imminent return of the Lodge was reported.

“When we got into the building, we realized it wasn’t just a fix-it-up, it was a tear-it-down,” said Martin. “It needed a new roof, ceiling, plumbing, electricity. Everything. It took a year-and-a-half.”

In the meantime, Martin kept the Black Lodge brand alive. For the past five years, with filmmaker partner Mike McCarthy, Martin has been booking the monthly “Time Warp Drive-In” series at Malco’s Summer Drive-in. In exchange for storage space at the Central Library, Black Lodge hosted some parties dubbed “Pandemonium” in the empty upstairs space in the Downtown Cossitt Library. (While in limbo, the collection lived in other places: The basement of First Congregational Church in Cooper-Young, a rented storage unit and finally at Crosstown Arts.)

This past Halloween and New Year’s Eve, Black Lodge sneak-previewed their new digs with some tactical-urbanism-style parties at the work-in-progress space on Cleveland.

Along the way, Martin found a group of new partners with skills to help make the more expansive vision of the new Lodge a reality. Martin’s the movie guy, while new co-owners Danny Grubbs (operations), Will Scheff (band booking/stage management), James Blair (chef/kitchen management) and Josh Argo and Barrett Rowan Argo (sound and lighting design) bring different skills to the venture.

This spring, a Blockbuster Video in Bend, Oregon, made news as the last franchise left in a chain that once dominated the industry world-wide.

In a long-shrinking business, the few traditional video stores left tend to be non-corporate leftovers in smaller towns and declining suburbs. Family Video, an Illinois-based chain, is the industry’s largest current operator, still claiming more than 500 stores in 20 states, in places such as Shelbyville, Tennessee (its only store in the state) and Rolla, Missouri.

But in bigger cities, video stores aren’t so much holding on as reinventing themselves.

“My main inspiration came from the fact that every major city already has this,” said Martin.

He’s referring to something like Video Vortex, a back-to-the-future video store companion to Alamo Drafthouse movie theaters in Brooklyn, San Francisco, and Raleigh, North Carolina.

A fourth Video Vortex opened in Los Angeles this summer, described by the Los Angeles Times as a “video store, bar, arcade, board game hub, and retail store.” It’s partnering with Santa Monica’s famed Vidiots, which closed its doors in 2017 and became Vidiots Foundation. Vidiots is now planning to reopen a physical space.

“All the major video stores have a choice,” Martin said. “Either you go non-profit as an educational provider or you move into doing screenings and bands, and the money comes from what you get on beer, wine and food. We thought about the nonprofit route, but in the end we decided to go for it.”

At the new Black Lodge, a 20-foot screen at the back of the room rear-projects movies with crystal clarity, with a sound system Argo designed to equally serve film and live bands. Movies are always playing — the Christopher Reeve-starring “Superman” from 1978, the 1983 Canadian beer comedy “Strange Brew” and a Neil deGrasse Tyson science doc were running during different visits last week. And, especially at night, the movies can be seen through the Lodge’s big windows while driving past. (“We like that,” Martin said.)

The open space is designed to be modular. Curtains can separate the movie rental collection from the theater space if a quieter environment is wanted for programmed screenings. The racks are on rollers and can be moved out to open up the full room for larger events.

Black Lodge has partnered with Rec Room gaming wrangler John Morgan to supply arcade games, which Martin hopes to have installed in the coming weeks.

While this has been a “soft” opening, Black Lodge held a “Club Crystal Lake” dance party this past Friday (the 13th), screening the related 1980s “slasher” series. Planned events for later this month include cult-film-connected actor/musician Jon Mikl Thor on Sept. 20 and the Italian art-rock band Goblin on Sept. 23. The latter will reproduce their score for the Dario Argento horror classic “Deep Red,” playing along with a screening of the film.

“We’re not rich,” said Martin about not opening at full speed. “The best thing we can do is get the video store and the venue up and start doing shows and parties and do what we call phase one.”

Eventually, Martin hopes to have nearly nightly screenings, concerts or other events, mentioning small-scale theater, stand-up comedy and burlesque shows. A kitchen will be installed in “phase two,” planned for sometime early next year, with Blair providing “stoner bar food with vegan and vegetarian options.”

If all of this programming is essential to the economic survival of a video store that can no longer afford to be only that, it also enhances what Martin sees as one of Black Lodge’s reasons for being: To provide the kind of third space where people with shared affinities can gather.

At a time when physical media is imperiled, independent book and record stores have maintained relevance by serving a similar function.

“It’s become harder to find places that encourage social interaction and talking,” Martin said. “The video store, like a bookstore or record store, was that for people. You were around people you didn’t know, but you clearly had a common interest.”

And that common interest — movies — remains the core concern and primary purpose.

Streaming has made physical media and the places that preserve it irrelevant? Are you sure?

“We’re already watching the fracturing of the streaming market. Disney will be first. Then Warner Media, then Paramount, then Sony. Eventually, if you want access to all the movies available via streaming you’ll need about $120 (a month) worth of streaming services,” said Martin. “None of them are going to play nice with each other.”

Even all that won’t get you everything. And that doesn’t just mean the kind of cult movies and rarities in which Black Lodge specializes.

Want to watch the 1985 John Cusack comedy “Better Off Dead”? Or Lynch’s 1990 Cannes winner “Wild at Heart”? Or the oh-so-quotable 1992 David Mamet adaptation “Glengarry Glen Ross”?

None of those titles — among countless others — are currently available on streaming services, according to the indispensable third-party site Just Watch. (And the most ubiquitous streaming service, Netflix, has all but abandoned older movies.)

All are on the shelves at Black Lodge.

“You think everything is at your fingertips, but it’s not,” Martin said.

While the Lodge was on its walkabout, Martin spent part of the time personally resurfacing the collection’s roughly 20,000 discs. (A process that literally strips the top layer from a disc, removing scratches while leaving digital information.)

He also converted roughly 2,000 movies from the Lodge’s VHS collection to DVD for rental, titles that have never been released on DVD or streaming.

There’s no new physical form likely to emerge for home film viewership.

“This is it,” Martin said. “If we don’t preserve it. You’re going to pay through the nose (for what remains available).”

And, for Martin, the video store, with its rows of covers you can peruse and pick up, isn’t just about preserving film history, but creating avenues for exploring it.

“Netflix’s algorithm only has the ability to suggest things similar to what you’ve already seen,” he said. “It keeps you in a niche of your already existing interests and asks you to stay there. A video store doesn’t do that. It invites you to notice just how much cinema you haven’t seen, and inspire you to maybe see some different things.”